Platoon sergeants, God bless them all!

Big Red Car here on another perfect Texas spring day. Ahhhh, on Earth as it is in Austin By God Texas, y’all.

The Boss was up in Lexington, Virginia recently to give a talk at an entrepreneurs event. Lexington is, of course, the home of his alma mater, Virginia Military Institute – a hard place to be, a good place to be from.

VMI has an expansive campus carry program including Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John at the foot of Stonewall’s statue. Those four cannons are combat veterans of the Mexican War and the Civil War. You get a rifle, a bayonet, maybe a sword, plus tanks, howitzers, cannons. Stonewall taught at VMI.

VMI is steeped in the history of the nation and the Civil War. The VMI cadets fought as a unit in the Civil War emerging victorious at the Battle of New Market wherein they conducted a bayonet charge across a muddy field and took Yankee cannons at bayonet point. They also took substantial casualties both killed (10 KIA) and wounded (45 WIA).

Lexington is also the home to Washington & Lee University, a bastion of Southern education. Rob’t E Lee is buried at W & L.

When you go to VMI, you look up your Brother Rats (classmates) who live in the area and you find a chance to swap some stories. The nature of your relationship is so close that if you haven’t seen them in 45 years you pick up right where you left off last time you saw them.

Which is a long way to say a discussion about platoon sergeants ensued. Platoon sergeants are the secret source which is applied to green shavetails to turn them into platoon leaders and soldiers. It is the beginning of a tutelage which is like a craft guild apprenticeship.

Shavetails

When you graduate from VMI, you receive your diploma (civil engineering) and your Army commission. If you have applied yourself, you emerge as a DAG (distinguished academic graduate) and DMG (distinguished military graduate).

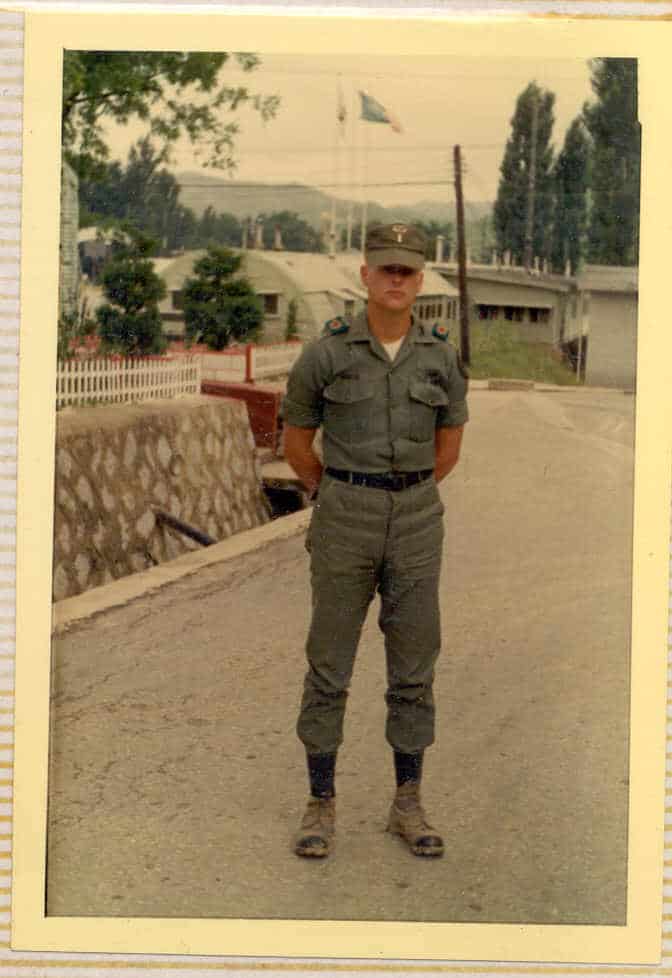

VMI graduate on graduation day. Pre-shavetail. DAG. DMG. Academic stars. Cadet Captain, Regimental S-1. Headed to EOBC, Airborne School, Ranger School.

You then go to your basic course (EOBC, engineer officer basic course), Airborne School, and Ranger School, whereafter you go out to your first assignment, hopefully overseas.

Then, you get a platoon. You will get a combat engineer platoon (The Boss) or an infantry platoon or some guns or a tank platoon.

You are a shavetail. Sure, you’ve completed the toughest training that Army has to offer. You’ve been to a great military school. But, you are still just a know-nothing shavetail.

Your platoon members, all 45-50 of them, know more about the business of soldiering than you do. In the combat engineers of that day, one of your privates might have an engineering degree from Lehigh University. The draft made this happen.

Then, you will meet your platoon sergeant.

Platoon Sergeants

Platoon Sergeants are the top enlisted man in a platoon. Four platoons per company, each has a lieutenant and a platoon sergeant. The company is commanded by a Captain.

Platoon sergeants have been in the Army about 15-20 years, been to war a few times, have trained a few platoon leaders, are closing in on retirement. Platoon sergeants are ass kickers.

It is the platoon sergeant’s sacred duty to turn “his” lieutenant into a platoon commander. Until he does, that platoon belongs to the platoon sergeant.

At first, when the platoon sergeant is talking to other platoon sergeants, he will say, “That fucking lieutenant of mine can’t pour piss out of a boot with instructions on the heel.” Yes, platoon sergeants say that kind of stuff.

The platoon sergeant is polite to his lieutenant within the confines of military courtesy, not more, but at least that. He will pretend that he listens to the lieutenant, but he really doesn’t.

Sometimes he will shake his head and tell the squad leaders, “I know what the lieutenant said, but this is what y’all are going to do.”

The Transformation

It takes 4-6 months for a platoon sergeant to figure out and train his lieutenant. It only works if the lieutenant understands what is happening. Some lieutenants don’t ever learn.

“When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.”

The most important thing for the lieutenant is to ask, “Sergeant Carter, you ever done this before?” You may be talking about taking out a minefield, blowing up a bridge, constructing a floating bridge to cross the Rhine.

“Yeah, about million times, lieutenant,” the platoon sergeant will say. There may be laughter.

“Tell me how it’s done,” the smart lieutenant will say.

At that instant, the platoon sergeant will smile to himself and think, “This dumbass second lieutenant has the sense to ask me before he issues orders to the platoon. Thank you, God.”

Do that enough times and you will learn how to be a platoon leader. Soon, the platoon sergeant, his work done, will actually allow you to command the platoon.

At the end of a year, the platoon sergeant will tell his peers, “That fucking lieutenant of mine is OK.” That is the highest praise he is capable of giving to a platoon leader.

The combat engineers are a small enough corps in the Army that you may serve with that platoon sergeant later in your career. In some other future posting, he will tell his peers, “I trained that Captain. He was a good platoon leader.”

Platoon Sergeants

The Boss had some great platoon sergeants. There was Sergeant Cotto-Perez who received the Distinguished Service Cross (second to THE Medal). When Sergeant Cotto-Perez got excited, he would speak in Spanish.

There was Sergeant Carter, the smoothest operator you ever saw. He would ask The Boss, “What does the lieutenant want the platoon to do today?” That’s Old School brown boot Army talk. There was a training schedule published, so Sergeant Carter was testing the lieutenant. “Did you read the damn training schedule, lieutenant?”

Sergeant Carter had played college football before his knee exploded ending his career. He was a real disciplinarian. The lieutenant had to constantly discourage him from smashing the soldiers with his fists. That platoon was very well disciplined.

The Magic Moment

Lieutenants and platoon sergeants will always recall the instant at which the lieutenant became the platoon leader and took charge of the platoon. In the Army, they do not really give you power, you have to take power. It is a magic moment.

In Korea in the 1970s, a platoon was taking out Korean War vintage minefields. These 20-year-old minefields had terrible maps because they had been put in in combat conditions. The combat engineers of the 2nd Cbt En Bn of the 2nd Inf Div were tasked with taking them out and putting new mines back in.

Each platoon got their sector. It was a wet, cold, snowy day.

The platoon sergeant broke out the mine detectors, big sweeping machines which signaled the presence of a mine with a high pitched noise.

The lieutenant said, “No mine detectors. I want the men down on their bellies, on ponchos, probing with bayonets.”

“Why?” the platoon sergeant asked.

“The maps are not good,” the lieutenant said. “The ground is frozen. I’m not sure that the mine detectors will be able to detect the mines. I want to see if the installation of the mines is predictable.”

Mines are put in in a specific pattern based on the location of an anti-tank mine at the middle of the cluster and anti-personnel mines surrounding it at specific prescribed locations.

“I think we should use the mine detectors, sir,” said the platoon sergeant in THAT voice. The voice which platoon sergeants use with dumbass lieutenants.

“No. I want the men to probe.”

“Shit.”

Half an hour later, there was an enormous explosion about a half mile away. Another platoon had used the mine sweepers, had missed a mine, somebody triggered it, the frozen ground sent a shock wave through the earth creating a sympathetic detonation of about an acre of mines. Legs, arms, bodies were raining down. All of the platoon was killed or wounded.

That night, when the platoon bivouacked, the platoon sergeant found his lieutenant.

“You made the right call today, lieutenant,” the platoon sergeant said sheepishly. There was whiskey on his breath. “I was wrong. Thanks for standing up for it.”

Of course, that platoon sergeant had taught that lieutenant to do just that — never risk the welfare of the mothers’ sons entrusted to him. Never. Ever.

From that moment on, that lieutenant was the platoon commander, the platoon leader. School was out. The lessons learned. He had taken power.

In the future, that lieutenant still asked the platoon sergeant if he had done something before he gave the orders to do it. He never lost that habit.

That lieutenant was The Boss.

So, wherever the Hell you are Sergeants Cotto-Perez and Carter, here’s to you. You taught me how to command soldiers. You let me make all the mistakes I needed to make. God bless you. Salute!

But, hey, what the Hell do I really know anyway? I’m just a Big Red Car.