Several years ago, I was at a funeral with a friend with whom I had served in the Army a million years ago. We had all been lieutenants — me, my friend, and the decedent — full of piss and vinegar, deployed overseas, sure of ourselves, though no logical reason why.

I had gotten a company command before the other two, but they would also get companies. Being a combat engineer company commander is as close to being a feudal Chinese warlord as a man can get in this life.

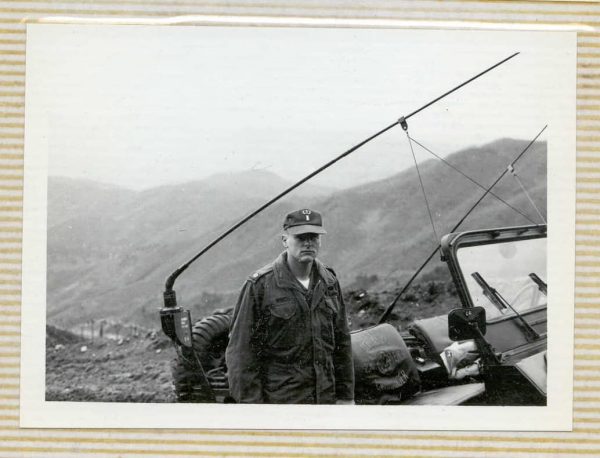

This was me at that time, just before I got the company. I was inspecting a road we were blasting onto the top of a mountain. That’s North Korea in the background.

We all graded well on our assignments as we had been prepared — degrees in civil engineering, Engineer Officer Basic Course top graduates, Airborne School, Ranger School, good sergeants to teach us our chosen trade, and to keep us between the guardrails.

The unit we were assigned to was a good one; the division was good; the duty was challenging; and we were earning the Queen’s shilling. I’ve read a lot of Kipling.

At that tender age, early twenties, we had found three friends in the mold of our own making. From a short distance we all looked the same and could be counted on to get the job done in a tight place. We took pride in our craft. We liked soldiering.

But, that was where the similarities ended.

The man being buried had stayed in the Army for thirty-five years, attained the rank of full Colonel (Full Bull, Bird Colonel) and had retired some years earlier. The other two of us, in the shadow of the Vietnam War’s end, had left after five years service not expecting there to be any market for our skills.

Before and after the funeral and the internment, my friend and I chatted about that long ago time. In the sun, the years peeled off, and we were those three lieutenants laying on our bellies looking into hostile territory and whispering. We had drank a few beers and exchanged a few secrets. We had been tested and passed, but our lives turned out differently.

The man being buried had been an orphan and told a story of his father abandoning him on the steps of an orphanage in a southern town as the sun was coming up on a frosty morning in which he remembers being able to see his father’s breath when he spoke.. It was a sad story, the kind of story that might make you rub the dust out of the corner of a suddenly moist eye. When asked when he was coming back to pick up my friend, his father had said, “I’m not.”

Such an experience marks a man for life.

My friend had lost a little of himself in the bottom of a whiskey bottle in tours of duty that tracked with the American military experience for those thirty-five years. A marriage had burst a seam from long periods of separation.

There was a child who died at an early age in a car accident.

“You never recover from that,” my friend had said when we spoke about it. “No father is supposed to bury his own son.”

My friend was falsely accused of a court martial offense, stood a court martial, and won at trial. But, the mental scars and the whispers didn’t subside.

He was passed over — unfairly — for things like the Army War College because of the residual memory of that incident.

He served with distinction in a couple of wars, had the medals for valor to prove it, and the “been there badges.”

He watched lesser men pin stars on, languished as a Colonel, knowing he would never be a General. Ever. He would be assigned duties that normally would be assigned to a General and he would discharge them flawlessly, but that Eagle on his shoulder would never become a star.

He lived with that slur, knew why it happened, and he didn’t always deal with it well.

He was insubordinate at times, but when the Army needed a real soldier to get something done, they would call him. The men who served under him adored him. In life, the respect of your subordinates is a currency few men trade in. He was an extraordinary leader in a profession in which leadership is the coin of the realm.

When he retired, he had made the mistake of out living many of his peers. He slid out of the parking lot without any fanfare or recognition for thirty-five years of faithful service.

He hung his uniforms up, put his medals in a drawer, and got a job. He grew into that job, found a second wife, had children, and kept his own counsel.

What the military couldn’t do to him, his health tried to do. He had multiple cancers, chemotherapy, radiation, surgeries, until finally the cancer decided it had had enough and went on to wherever cancer winters over when its been defeated.

The last ten years of his life, things began to fall into place — wife, family, job, financial rewards, kids.

Five years before he died, we bumped into each other and he said, “I’m happy. I really am.” We didn’t speak of his father and the orphanage or his struggles with alcohol, his dead son or his first wife, but I wished we had. I would like to have heard his take on those things. Had those wounds healed?

I told him, “I admire you. You stuck it out until the end. The world needs men like you.”

He laughed it off, but I could tell he was pleased. I was pleased to count him amongst my friends because it said something good about me.

We spoke of this at the funeral — my other friend and I. We spoke from the reference point of who we had once been — three lieutenants laying on our bellies looking into hostile territory with our binoculars and dreaming about what lay ahead for us.

I said to my friend, “Son-of-a-bitch was a survivor.”

My friend smiled, and laughed. We were once again lieutenants with our whole lives ahead of us.

“No,” he said, “he was a fucking warrior.”

Godspeed, Colonel. See you on the high ground.