As the CEO/Founder of a startup, you will develop practices that you know work. Many times, these practices will not be perfectly “normal.” They will reflect your own personal style or they will be things that you just know work.

These are what I call field expedients.

Back in the day, when I was a combat engineer officer overseas, I had a damn good sergeant who worked for me. We were blowing up old fortifications in South Korea just south of the DMZ. When we demolished them, we cut all the rebar with cutting torches, removed the concrete pieces with dozers, dug a big hole, and buried the detritus (reinforced concrete). I used to recover all the steel and send it down to Seoul.

Then, we rebuilt them — often in slightly different locations and to a substantially higher structural strength — to withstand then modern artillery.

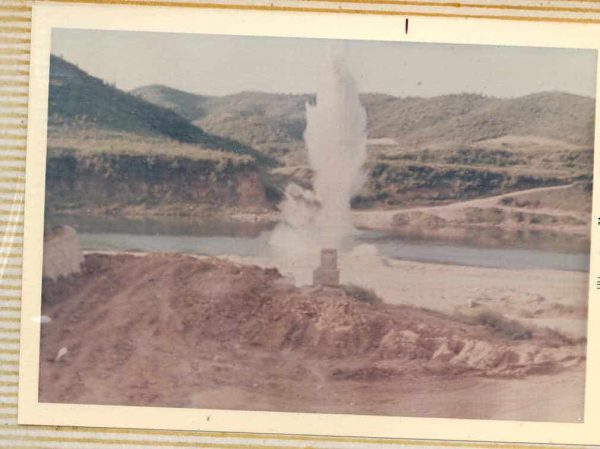

Here’s a picture of what it looks like when 100 lbs of C4 is exploded underneath a shallow bridge abutment. The bridge abutment was in the way of our river crossing site if we had to attack into North Korea. So, me and another sergeant used scuba gear and wedged 100 lbs of C4 under it and voila!

The first day we went up to the Z to blow up some fortifications at a river crossing, I calculated the charges to perfection — exact amounts to the individual stick of C4.

My sergeant looked at my calculations and said, “Wow, Lieutenant, you really know your stuff.” I beamed with pride because Lieutenants live to be praised by sergeants who have been in this man’s army for 20+ years.

When it came time to actually do the work, I noticed that my sergeant ignored my painstaking calculations and simply placed a whole case of C4 or two cases of C4 at the appropriate points.

After I inspected the installation and approved it, I handed the sergeant the handle to the blasting machine, we stepped back half a mile, and he turned the crank. BOOM! [There are few things as satisfying as blowing stuff up. It brings out the 8-year old in every man. It is, however, quite loud. We had to tell the North Koreans what we were up to so they wouldn’t think we were attacking.]

There was a cloud of dust.

We did this another thirty times until we had smashed all the fortifications. Then, we cut the rebar freeing up the concrete chunks before the dozers went forth and pushed the debris into a pile which was then carted off to where we had dug a hole with another dozer and two front end loaders. By the end of the day, there were no fortifications, the debris had been hauled off, and the hole was covered. The rebar spent the night in Seoul (I was an recycling environmentalist even then.).

As chance would happen, we were up at the Z rebuilding those same fortifications and I had occasion to chat with my sergeant. I asked him, “Sergeant Jones, I noticed that when we blasted those fortifications, you ignored my calculated amounts and used whole cases of C4. Why?”

The sergeant, who was a diplomatic chap, said, “Well, Lieutenant, that’s the way we do it in the real world. It’s called a field expedient.”

“Why?” Lieutenants, smart ones, are always asking their sergeants why they do certain things.

“Well, Lieutenant, if I had to cut open those cases of C4 to get the exact amount of C4 you calculated, it would have taken a lot of time. Then, I would have to wrap those charges into the right sizes which would consume a lot of duct tape (the skillful use of duct tape is an essential skill in the explosives racket). So, I just rounded it up to the next full case. This way, I know we have enough explosive. I know it will work. I know it will bust that concrete into smaller, more easily handled pieces. Plus, Lieutenant, we have access to unlimited C4.”

If you wondered where you taxes went in the early 1970s, this is where. I was profligate with C4 thereafter. Sorry. Not sorry.

You can use C4 for fishing. That truck is a 5/4 ton truck filled with 2,000 lbs of C4. You can tell from the soldier’s wet pants that he was fishing.

I thought about that. I recognized the wisdom of it. I embraced it, thereafter, as a field expedient. I took it as my own. I learned and put it to use.

The Supe

Once I was blowing up a bridge in summer training with West Point cadets. One of the rules for West Point cadets and explosives is to ensure you end up with the same number of cadets AFTER the training exercise as you start with BEFORE the training. The administration is very much a stickler on this rule.

I taught the cadets how to calculate the exact amount of explosive for a rather stout timber trestle bridge (which I had taught them how to design, build and which we built). The bridge could hold two M60 tanks at the same time. It was a stout bridge.

The day of the appointed demolition of our bridge, I taught the cadets my field expedient.

“While it is always useful to know exactly how many pounds of C4 are required, it is a field expedient to just round up to the next whole case. You can even double it if you are in doubt. This will save you time and it is how the combat engineers do it for real in the field. You will look savvy and wise.”

As fate would have it, the Superintendent of West Point arrived with some foreign officers to observe Demo Day (you thought only startup accelerators had Demo Day?). I had to ask them to take a position fairly remote from the bridge. The Supe was a little perturbed with me, but as the demo officer, I was in charge of the range. [This is a little fiction as he was a 4-star General and I was not.]

I let one of the cadets crank the blasting machine; the bridge went up. The bridge was reduced to pixie dust and tooth picks. There was a down wind cloud of little sticklets falling in the direction of the viewing stand. I also liked to use a lot of C4 because cleanup was facilitated.

The next week, I received a summons from the Supe’s office that he would like to have a chat with me, “. . . if it was convenient.” I checked my calendar, found a good slot (like immediately), drove over to the Supe’s office, reported, saluted, and we had a chat. He did not invite me to take a seat. It was not that kind of chat.

He had seen one of those Demo Days before and he wanted to know what was different with my Demo Day. I explained the field expedient aspect of the training exercise. He listened wordlessly — he was an Infantry General.

“So,” he asked, “that’s the way you would really do it in the field when you’re a combat engineer?”

“Yes, sir.”

He dismissed me. I got a very good OER (officer efficiency report) for the summer training (I had balanced the number of cadets in the before v after sweepstakes.) and the Supe went to the trouble to endorse my OER saying words to the effect that I had taught the cadets “real world” solutions to challenging missions. It is very unusual to have a 4-star endorse your OER. It is a good thing.

That’s when I fell in love with the field expedient.

In business, I used to conduct an Anonymous Company Survey whenever I sensed there was a disturbance in The Force. I batted 1.000 on my spider sense. The Anonymous Company Survey was also a field expedient. I always identified the problem — sometimes I fixed it. Sometimes, I acknowledged it, but told the team that I was not going to do or change anything, but I understood the issue.

In your endeavors, pay attention to discovering field expedients. If you have to blow up a bridge, fortifications, a bridge abutment, round up to the full case, double it, and crank it.

But, hey, what the Hell do I really know anyway? I’m just a Big Red Car. Happy weekend to y’all. Please call your parents — they are so damn easy. [Hey, that might be a field expedient?]