Being born the son of Leonard C Minch (CSM, USA-Ret) has been the luckiest happenstance of my life. He was and is, simply, the best man I have ever met or known. His moral compass was welded at true north and his example of how to live, and die, was exceptional. He confronted life face to face, he mastered it, and he died on his own terms.

Last Thursday, at 6:20 AM, he drew his last breath. I am devastated and completely defeated for the first time in my life. I write these words between tears for my loss. I am very selfish that way. He would laugh at me and say, “I was 97” as if that would explain it all.

In a world of bullshitters, my father was a doer. When he entered a room, standing almost 6′ 4″ tall, he was in charge. It was part his carriage and confidence. He did nothing to create that sense. It just happened. It was perfectly natural. I was raised in that shadow.

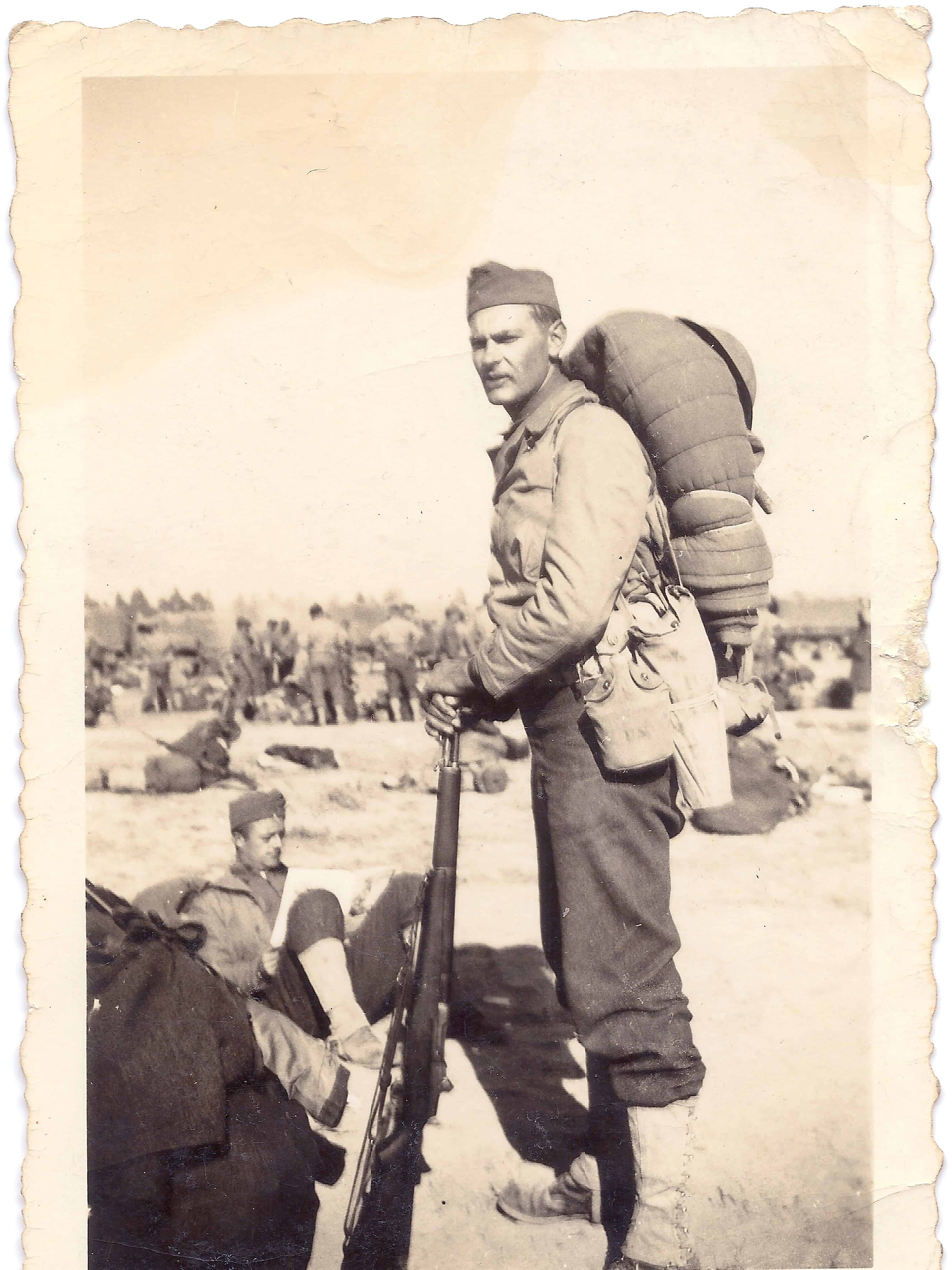

At the tail end of the Depression, he joined the Army to see the world and became enmeshed in World War II. My favorite picture of him is this one.

This picture was taken three weeks before Pearl Harbor and the Army was on maneuvers. He was 22 years old and already had begun to move up in the ranks. He’s leaning on an M1 Garand rifle, the type he would carry for much of the war in Italy and a rifle he taught me to shoot and the same rifle I would have at VMI years later. Soldiering would be a common bond between me and him. It was the family business.

In Italy, he was the platoon sergeant of a gun section — two 105mm howitzers — in Cannon Company of the 361st Infantry Regiment of the 91st Infantry Division which fought the Germans — he always called them Krauts — from below Rome all the way to the mountains at the top of Italy. He was constantly fighting against the 4th Parachute Division. He said they were “tough bastards” which said something about him and his unit as they drove them ever northward. The war in Italy was some of the toughest fighting the Allies engaged in as they fought through the winters on very difficult terrain.

When the platoon leaders were being killed off, the regimental commander summoned him and told him he was to be commissioned as an officer. My Dad wasn’t too wild about the idea as the vacancy had come about in a manner which seemed to suggest a high rate of mortality. The regimental commander persuaded him to put on the bars of a lieutenant. His platoon — gun section — was very proud of him though he had to be transferred to another gun section.

He fought those guns against the Krauts at every little river crossing, mountain pass, and hill sometimes firing direct fire against Kraut 88s, deadly German guns. At the end of the war, he had a Bronze Star, a Combat Infantryman’s Badge, and a Kraut railway battalion — prisoners of war.

He came home from the war, met a beautiful woman, and married her three months later. The war made everyone move at a faster pace. He said it was very simple — she was the most beautiful woman he had ever met. They met at Camp Kilmer (she was in the Army also), where we would live as a family later on.

My father and mother were married for 57 years until my mother died. I hope my father is with her right now. They are having a blast, I am sure.

They had three children and were an organized team in raising us. Mom was the disciplinarian which may strike some as odd but she had been in the Army and was from a big Irish family and knew how to keep us in line.

My father never had the advantage of an education and therefore valued it immensely. His three children all earned MBAs and his expectations were clear from the start. On an Army paycheck, he sent us to private schools and expected us to perform. If we did not, there were consequences.

Any son lives for the approval of his father. I was no different. I recall with great clarity the three times when I received it in an undiluted fashion. They surpass all other accolades and triumphs since then as I valued his opinion above every living person I have ever met.

He was a great father, not a friend but a parent. The things he taught me to do and allowed me to do would require hours to list. I remember shooting the same Garand M1 rifle when he was teaching ROTC at Rutgers University. When I went to VMI and was in the Army thereafter, I never needed an additional second of instruction. His lessons were complete and I could shoot with deadly accuracy.

More importantly, he taught me to do things on my own. It wasn’t obvious and it wasn’t programmed. It was perfectly natural and instinctive. He shaped me and drove me in a certain direction but I never felt his hands on me.

I was convinced I was going to go to college and study Latin and Greek — I had been reading the Punic and Gallic Wars in Latin with the nuns. He asked me one night, “What kind of a job do you think you’re going to get with a degree in Latin and Greek?”

A week later, he said, “During the Depression, the only guys who made out were the engineers. They could make change in their heads while selling apples.”

In three sentences, he shaped my life in a perfect direction. That was his genius. I went to VMI and studied civil engineering, the third luckiest happenstance in my life.

We never talked about soldiering until I was ready to go into the Army and then he gave me a primer of about five dinners in which he told me everything I was ever to need to be a good officer. It really was all I ever needed to know condensed to its essence.

When I would get my OERs (officer efficiency reports), I would send them along to him. I waited with baited breath for his reaction. Once I got a spectacular OER and he smiled. “What did you expect?” was all he said. In everything I have done since, it was only his expectations that I sought to meet.

My father loved two fabulous women — my mother, Rita, and Corinne, his current wife. He was very lucky. Corinne prolonged his life after my mother died and I am grateful for her love and care of him. She was there as he drew his last breath.

My father lived the American Dream and imbued his family with it. He married twice for love. He loved and was loved by two extraordinary women. He raised three good kids and sent them along on a higher road than he had been able to climb. But it was his doing, not ours. He never had a great paying job but he saved his money, invested wisely and shrewdly (my mother gets a lot of the credit here as she ran a very tight ship), and became a multi-millionaire.

He died of the complications of a foot infection. One day, he woke up and his foot had turned red. The doctors were unable to overcome the infection with IV antibiotics and after a two week stay in the hospital, he made the decision to die on his own terms. There was a family history of diabetes and amputation and he wanted none of it.

He entered hospice care and forty three days later, he died.

In that time period, the family had an opportunity to say good bye and he had the opportunity to clean up a few loose ends and to organize his affairs. I went to see him for two protracted periods of time and we spoke about everything knowing it would be the last time we ever spoke. We had great talks. I wrote him a letter in which I was able to express many of the sentiments that I have expressed in this blog post. Things I could never have said in person as I could not have maintained my composure. He knew how much I loved him and that is a great blessing to me.

We re-fought the entire Italian campaign.

My son and daughter, who is to be married in three weeks, visited with him. He was alert and sharp. Underneath the conversation was the reality that he was going to die but in the last weeks of his life, he lived well. I am happy that they were there to see his dignity and courage and toughness. Getting old is not for the faint of heart but the indignity of death really sucks.

Only in the last few days did the infection begin to do what wars, combat, cancer, heart surgery, ulcers could not. He is the toughest man I have ever met. As his breathing began to lapse — down to four breaths per minute when they summoned me the first time — he fought back. One of the reasons he liked VMI was that when he taught the VMI cadets hand to hand combat during summer camps, they were gentlemen and would offer a hand to their victims. I could feel him going hand to hand with death. He knew he was going to die but he wasn’t going out without a fight. He fought — his chest gurgling with congestion — until, literally, the last breath.

I was summoned twice and each time he fought through it. The last time, Corinne left the room and when she returned, he breathed his last breath as if not willing to pass until she had returned.

I sit here at this instant unable to imagine how I am going to go on without him but knowing I must and that he would be laughing at me. He would be saying, “I was 97 years old. I had a great run. What, are you taking stupid pills?” Stupid pills were a joke between us that was more than a half century old.

I am totally and completely defeated at this instant, something I have never been before in my life. I am simply going through the motions of pretending to be alive. I know that in time, I will rally as his son would do but for now I am lost and adrift. I do not want to be found for a little while and then I will return to the state that has always propelled me forward — trying to win that man’s approval because that is what sons do. They strive to win the approval of their fathers. And my father? He was and is the best man I have ever known.

Here is a picture of me at the same age as my father in the picture above. He liked this picture as I had mud on my boots, something he said officers didn’t get enough of.

Rest in peace, Dad. Thank you.